Constance Tenvik, Building Worlds

Curator Tominga O’Donnell explores some of the precursors to Constance Tenvik’s new installation at MUNCH as part of the museum’s SOLO OSLO series.

Photo: Ove Kvavik / Munchmuseet

Constance Tenvik is an artist who expresses herself in a range of different mediums. There is a breathtaking breadth to her practice: not only does she use the traditional mediums associated with visual art – painting, sculpture, drawing, video, performance – but also writing and interviewing, tailoring and design collaborations, singing, dancing and acting. Among her references, Tenvik cites a number of artists who did different things as an extension of their artistic practice: Paul Klee’s hand puppets, Pablo Picasso’s scenography for Jean Cocteau, Sonia Delunay’s costumes.

With any essay on Tenvik there is the potential for going down rabbit holes that risk ignoring a central aspect of the artist’s work. For the installation at MUNCH, I have, therefore, selected – with Tenvik’s guidance – four previous exhibitions that can be considered part of the same body of installation work. All four depart from existing literature and expand into a highly personalised universe of multiple artistic mediums under the umbrella of one narrative. This approach has become central to her practice and can be seen in the following previous solo exhibitions: Gesamtkunst With Myself at Loyal Gallery Stockholm (2017); Soft Armour at UKS/Kunstnernes Hus (2017) and A Journey Round My Room at Astrup Fearnley Museum (2019), both in Oslo; and Aloof Periwigs at Anat Egbi in Los Angeles (2022).

Gesamtkunst With Myself

The first word of the title of this exhibition evokes the German term for «total work of art» associated largely with the composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883). He advocated for uniting poetry, drama, visual art, and music into what he considered “total theatre”. In fact, the text that acts as the touchstone for Tenvik’s Gesamtkunst With Myself is the story of Tristan and Isolde from Wagner’s eponymous opera, first performed in 1865, and based on a medieval Celtic legend of two young people who drink a love potion intended for the king and fall in love. It is perhaps one of the most revered stories in the history of Western opera. Evoking it suggests a lineage of so-called high art. However, the potentially self-aggrandizing sentiment in the first word of the title is undermined by the phrase “with myself”. There is something a little pitiful in the image of someone creating a “total work of art” by themselves or on their own. It is also a bit of an oxymoron – the prime examples of gesamtkunstwerk have invariably involved lots of people: staging operas, building cathedrals, putting on Greek plays with large choruses. It’s hard to unite all the artforms by yourself, even if it starts as a solo venture; others usually have to come to deliver the “total work” to an audience.

Constance Tenvik, Gesamtkunst With Myself (2017), Loyal Gallery i Stockholm. Courtesy of the artists and Loyal Gallery Stockholm.

In Gesamtkunst With Myself at Loyal Gallery in Stockholm Tenvik installed a video in the centre of a bright turquoise floor, surrounded by paintings, drawings, and clusters of textile works on white walls or draped on sculptures. Over three acts, Tenvik played all the parts including the scheming queen, the princess Isolde, Tristan, a ship, its sail, the sea, a fanfare trumpetist. The surrounding installation acted as tentacles for the video as costumes and props recurred in the form of cuddly toys, fried eggs and snippets from the poem of Tristan and Isolde. I never saw the exhibition, but when I look at these bright colours and knickknacks with a cherubic charm, I am reminded of another exhibition I saw in Stockholm recently, that of American artist Vaginal Davis at Moderna Museet. The link is not an obvious one, Davis is far more direct in her innuendo, crasser in her campness. Nonetheless, there is a mischievous vein that run through both artists’ practices and a kind of strange or estranged allure. Drawing on made-up characters and multiple personas with a slap-dash aesthetic, Davis and Tenvik both display the spirit of New York-based queer experimental filmmaker and performance artist Jack Smith (1932–1989). They toy with language and do not letting medium specificity or means stand in the way of playful expression. With her connections to the US through her MFA at Yale and exhibitions in New York and Los Angeles, these artists are a natural part of Tenvik’s referential horizon.

Soft Armour

Soft Armour was an exhibition in 2017 when UKS – the Young Artists’ Society occupied the downstairs gallery of the venerable Oslo institutions, Kunstnernes Hus, in addition to their own space in St. Olavs gate 3. The touchstone for this installation was not a text, as such, but a tournament, namely the reenactment of a medieval joust at organised by the Earl of Eglington in 1839. The Eglinton Tournament, a romantic historical reenactment inspired by Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe (1820), was a grand failure as the spectacle and its 100,000 visitors were drenched in a torrential downpour. As in Gesamtkunst With Myself earlier that year, the centre piece of the installation at Kunstnernes Hus was a video, flanked by playful props and paraphernalia that extended the video’s visual world into the space of the gallery – gym horses standing in for equestrian jousters, the titular soft armour of textile breastplates and gauntlets, and novelty pants with heart logos adorned with pubic hair. This time, Tenvik was not in front of the camera, but enlisted friends and family to play the parts of lords, barons and marquesses and other aristocrats in the film. Musician Jenny Hval played the lead character of the Earl of Eglinton and also provided the soundtrack. A gesamtkunstwerk with other people this time, if that is not a tautology.

Constance Tenvik, Soft Armour (2017), Kunstnernes Hus i Oslo. Courtesy of the artists and Loyal Gallery Stockholm.

The exhibition at UKS’s own premises was revealing for what piqued Tenvik’s interest in such a strange event as a romantic reenactment of a medieval jousting tournament, based on a fictional and imagined source – a simulacra spectacle with no real original. It was renowned for its failure at a time when Europe has seen the revolutionary unrest of the 1830s, and seemed to capture how out of touch the English aristocracy was. The opulence and the foolish romantic sentiment behind the staging of the event was illustrated in the UKS space at St Olavsgate 3 with mannequins wearing the knights’ costumes, excerpts from the banquet menu, including roast peacock, alongside a trophy made for the tournament winner that never was, and a number of mind maps and preparatory sketches from Tenvik’s work with the exhibition. These offer a fascinating insight into her attraction to such an historical event: she seems drawn to nostalgia as a complex phenomenon and to the “poetic exaggeration” of chivalry. Yet, the event she sought to restage was itself an epic failure, making the whole venture absurd. Tenvik’s pastel universe was a joyous, theatrical celebration of folly.

Constance Tenvik, Soft Armour (2017), Unge Kunstneres Samfund i Oslo. Photo: Roderick Hietbrink. Courtesy of the artists and Loyal Gallery Stockholm.

A Journey Around My Room

In 2018, Tenvik was selected for an exhibition of six solo presentations of young artists at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo. The resulting installation A Journey Around My Room was inspired by the French book by Xavier de Mestre. In the original text, written in 1790, a young soldier is confined to house arrest for illegally participating in a duel. For six weeks, he recounts tales of his rooms, parodying popular books at the time such as A Voyage Around the World by Louis de Bougainville (1771). In Tenvik’s installation, the gallery was transformed into a pastel boudoir, complete with a large sunken bed, stuffed toys, silk pyjamas and a dressing gown dedicated to the philosopher Simone Weil. A pale purple wallpaper with fried eggs covered one section of the space, whilst the main wall was clad in a large jacquard tapestry of moons and suns dancing over a red backdrop. There was a sickly sweetness to the space, which to me again found resonance in Vaginal Davis’s pink teenage bedroom at Moderna Museet – bar the giant penis in the bed, that is. Tenvik’s was an installation that invited participation, and soon the thick white carpet was covered in footmarks, the bed unmade, the costumes draped willy-nilly.

Constance Tenvik, A Journey Around My Room (2019), Astrup Fearnley Museum. Photo: Christian Øen. Courtesy of the artists and Loyal Gallery Stockholm.

Aloof Periwigs

A periwig is an archaic term for a wig like the ones worn by judges in England and Wales. In Tenvik’s exhibition at Anat Egbi in Los Angeles in 2022 the titular headdresses were placed on top of steel sculptures – umbrella stands, ball gown corsets and cake stands – painted in pale pastels of purple, green, and different shades of pink. These presented themselves as unfinished characters, half storage vessels and half inanimate actors in a play watched by a series of portraits hung on the surrounding walls. The play in question was Amadeus (1979), which Tenvik had been approached to create the scenography for in 2020 for a production at a Norwegian theatre. She was never awarded the commission, but during the course of her research into the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart she became, by her own account, obsessed with his life and work. The subsequent exhibition became a series of props without a play, a cast of characters without a plot, a dance without movement or music. In a fortuitous twist of fate, the work made its way back to Norway, as six of the characters were acquired by the Norwegian National Museum.

Constance Tenvik, Aloof Periwigs (2022), Anat Egbi Gallery, Courtesy of the artists and Loyal Gallery Stockholm.

In the Los Angeles presentation, the scenes played out in the surrounding paintings were those of stylised portraits in lurid palettes and wild parties, depicted in garish green hues with the sharp contours of hair and noses. Portraiture in Tenvik’s painting practice acts as a transformation of the subjects into a world of cavorting bodies, elongated limbs and exaggerated expressions. The spatial composition is evocative of Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911). The laws of gravity are suspended, bottles, bananas, bags and books seem to float against brazen backdrops. Hands are oversized and legs twist awkwardly as feet seem to be on a frolic of their own. Like Alice Neel’s portraits, they are based on real people, and often painted in Tenvik’s home with an intimacy that translates into tenderness on the canvas. However, Tenvik does not provide verisimilitude but a ticket to ride into a different world – a universe of her own making, which is remarkably consistent for all its flouting of traditional painterly rules. It is a form of world-building that is characteristic of Tenvik’s practice and that gains a rich three-dimensionality in her installations.

The Birds

For her exhibition at MUNCH, Tenvik has used the ancient Greek comedy The Birds by Aristophanes from 414 BCE as a backdrop for her new installation. In The Birds, the world is divided into three. Two men, Pisthetaerus and Euelpides want to escape from the human world of Athens, where they are burdened by debt, constant quarrelling and litigation. Enlisting the help of Hoopoe, a hybrid bird-human, the two men manage to ascend to the bird world, where they convince the birds that they are the true gods. They establish a city in the sky, which they name Cloud-cuckoo-land, and immediately set about building the city with the construction materials of their own, human world – stones and bricks, rather than straw and feathers. Soon, more people want to follow and settle in the bird world. They build stone walls that create barriers to the world of the gods and prevent them from receiving sacrifices. The Olympian gods become starved of their customary offerings, and eventually their frustration leads them to confront the birds and their de facto new ruler. The resolution in the play comes in the form of a wedding, and the handing over of Zeus’s sceptre to Pisthetaerus. The Birds is often seen as a satire over the failed Athenian military expedition to Sicily during the Peloponnesian War (415–413 BC). By returning to a text that is nearly 2500 years old, Tenvik shows the enduring relevancy of literature, while using the Aristophanes as a springboard to invoke contemporary concerns.

In Tenvik’s exhibition, the human characters are given new names based on their Greek meanings: Mr. Convincing (Pisthetaerus) and Mr. Hopeful (Euelpides). They are represented in the exhibition through steel sculptures, painted in pastel blue and light green, and adorned with wigs and textiles. They resemble the sculptures in Aloof Periwigs, but are more clearly human with pronounced facial features, feet and hands, rather than functional objects standing in for human form. Their world is marked by an ornate and multi-coloured gate at the entrance to the installation. Metal is a prominent material in this initial section of the exhibition, including a clothes rack with wings, representing the stage before the humans’ ascendancy into the world of the birds. The aluminium wings are clad in brightly-coloured plumage made from deconstructed shuttlecocks. In a departure from her earlier brightly-lit installations at Loyal and Anat Egbi, the lighting at MUNCH is more atmospheric and theatrical, and the walls painted a dark plum purple.

Constance Tenvik, Tio-Tio-Tinx, 2024 © Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ove Kvavik / Munchmuseet

Tio-tio-tinx

The onomatopoeic title of Tenvik’s exhibition is derived from the Greek play’s language of the birds. Their world forms the centrepiece of her installation and is represented in four large digital jacquard weavings. Each textile panel is a translation of a Tenvik painting into digital patterns and threads, which rekindled her collaboration with the wool factory Innvik on the west-coast of Norway. They depict strawberries on Greek columns against a pink backdrop with white clouds, reminiscent of the fried eggs of A Journey Around my Room; a somersaulting human on a dusty peach background with the characteristic pants from Soft Armour with pubic hair decoratively adorned on the outside. Beneath the topless gymnast with breasts akimbo, three hybrid bird/humans – harpies – depicted in royal blue are captured mid-dance, seemingly stunned by being discovered. Their kin – humans in various stages of metamorphosis into birds – fill the next weaving with their cavorting and jostling. Entwined bodies seem to ascend from the bottom of the image with its brick pyramids towards the heavens where they become increasingly more birdlike with more pronounced plumage – deep blue bodies with white wings. This intensity of colour is also evident in the final weaving with its orange-red background. This is the most allegorical of the four, evoking a Dionysian scene where a young athletic male in a sarong in the foreground is juxtaposed with an old scowling philosopher in the background. Between them stands another character clutching a mask, a symbol of the theatre, or has he perhaps just revealed his older compatriot’s Janus Face.

Constance Tenvik, Tio-Tio-Tinx, 2024 © Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ove Kvavik / Munchmuseet

Photo: Ove Kvavik / Munchmuseet

Starving gods

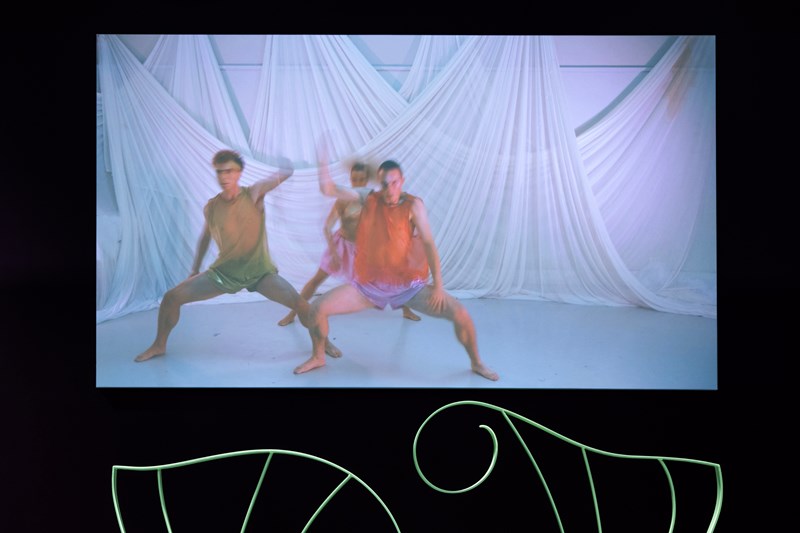

The final section of the three-part installation shows the world of the gods. They are framed by black and white jacquard weavings with the distinctive profile depictions of gods morphing into clouds. Their contours echo Tenvik’s distinct hand, evident in so many of her drawings and sketches. In a departure from her earlier work, the video is not the centrepiece of Tenvik’s installation, but rather a culmination of the audience’s movement through the three worlds. The video was filmed in Edvard Munch's studio at Ekely and shows the twelve Olympian gods' response to their lack of sacrifices and adoration from the humans. Each character has a costume designed by Tenvik: cascading pale purple tentacles for Zeus in his tight dress with a revealing split; gold shorts and a diaphanous yellow cape for Hermes; a frilly toga and lavishly decorated wig with flowers and grapes for Dionysus. Tenvik has created an imagined moment in the story of The Birds where the gods are on the brink: they have lost the adoration of the humans, are starved of attention and their omnipotence is waning. Their response is a blend of petulance and despair. The pronounced strings that dominate Ellen Allien’s pulsating soundtrack reflects this fluctuating emotional state.

Constance Tenvik, Ode to the Starving Gods, 2024, Video, 08 mins. 25 sec, © Constance Tenvik, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ove Kvavik / Munchmuseet

Space travel and terraforming

In the play, the birds are convinced by Pisthetaerus to upset the existing order of worship, seemingly elevating them to the status of gods. However, as he says early on, he is really “meaning to settle and colonize”. It is a familiar story of expedition, exotification and exploitation of the “other”, whether animal or human. It is a tale that resonates today, over the past centuries, having divided up the earth and the seas, airspace has been claimed by different countries. The American flag was planted on the moon in 1969. The next venture seems to be to colonize the planets with billionaires such as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk lining up to stake their claim to extraterrestrial territories. Their rhetoric is escapist, as Bezos told the International Space Development Conference in 2018: “We will have to leave this planet, and we’re going to leave it.” These “we”, of course, is a small group of high net worth individuals who can afford commercial space travel. Such sentiments have become more commonplace as a consequence of the acceleration of the climate crisis, but they are by no means new. It is 50 years since Ursula K Le Guin published The Dispossessed (1974). In it, an emissary from Terra explains “My world, my Earth, is a ruin. A planet spoiled by the human species. We multiplied and gobbled and fought until there was nothing left, and then we died.” There is a danger in the fatalist thinking that our world is ruined already and that the only option is to take a select few humans to another planet to start over. It means that there is no need to stem the extraction and exploitation of limited resources, no need to halt the heating of the earth’s atmosphere.

The constant return to colonialist, exploitative approaches to “new” territories is testament to a failure of imagination. Artists in every medium – from science fiction to painting – have posed new potential trajectories for humankind, imagined other worlds and alternative ways of being – here on earth. Drawing on now five Tenvik installations, I see that her artistic imagination is increasingly founded on a form of community building. From Gesamtkunstwerk With Myself – a seemingly lonely venture – she has built up constellations of people who participate in her work with remarkable exuberance. This is testament to Tenvik’s ability to capture the imagination of her collaborators with a strategy of joy, which to me is fundamentally queer. It is about building chosen family relationships through love and laughter, about celebrating a sense of being outside the heteropatriarchal norm – together. Tenvik’s promiscuous use of different artistic mediums, a borderline obsessive approach to research and omnivorous intellectual curiosity makes her an artist with the capacity to mobilise on many different levels. The world she has built at the top of MUNCH, 50 meters above ground, is part of ascent that is both decadent and critical – a joyous leap that elevates and engages both mind and body.

Cited works:

Aristophanes, The Birds, translated by John Hookham Frere (Cambridge University Press, 1883)

Constance Tenvik, Buffeen (Oslo: Forlaget Fanfare, 2016)

Ursula K Le Guin, The Dispossessed (1974)